Eighty years ago today, Lev Davidovitch Bronstein, better known as the Communist revolutionary leader Leon Trotsky, died in a hospital in Mexico City from fatal head wounds sustained the day before when a Stalinist agent, Ramon Mercader, attacked him in his study with an ice pick. Trotsky's guards had almost beaten his assailant to death, but while still conscious, he ordered them to stop and after a spell in jail Mercader was to end up spending many years in idle retirement in Cuba at the expense of the USSR.

It was the end of an eventful life. Born to relatively affluent farming parents in the southern Ukrainian Jewish community, Trotsky grew up observing the gross inequalities and violence of Imperial Russia. He became interested in the radical socialist ideas sweeping Russia at the time at university and quickly got into trouble with the Czarist authorities. He was jailed and exiled twice to Siberia, escaping both times and adopting the name of one of his jailers firstly to aid his flight and later to be his revolutionary codename (just as Vladimir Ulyanov became Lenin).

In 1901, anticipating the century ahead from his readings of Marx and Engels, he foresaw better times and devoted himself to struggle for them:

As long as I breathe I hope. As long as I breathe I shall fight for the future, that radiant future, in which man, strong and beautiful, will become master of the drifting stream of his history and will direct it towards the boundless horizons of beauty, joy and happiness!

Trotsky's odyssey took him from the Russian forests to Germany, Switzerland, Britain, Belgium, France, and the USA in pre-revolutionary exile. He first returned to Russia in 1905 where at the age of just 26 he latterly headed the first St Petersburg Soviet (revolutionary council) during the revolutionary insurrections that nearly toppled the Czar that year. Previously a member of the Russian Social Democrats, a Marxist party, he had stepped back following the split in 1903 between the Bolsheviks under Lenin, who pushed for a highly centralised party to prepare to act as a revolutionary vanguard, and the Menshevik wing headed by Martov, which argued for a more decentralised organisational structure and a more gradualist approach to change.

For all that Trotsky was committed to socialist revolution, he was at least initially one of the more pragmatic members of the movement, working to reconcile the two wings and maintaining a degree of independence almost right up to the Communist October revolution. He joined the Bolsheviks in spring 1917 when the Russian Empire had collapsed and the liberal regime that had replaced it was veering between repression and chaos. With a reactionary coup narrowly defeated by armed workers, Trotsky headed the Military Revolutionary Committee that co-ordinated the seizure of the Winter Palace and dissolution of the Provisional Government of Kerensky (a bombastic character, much misrepresented in the West in subsequent decades as some tragic democrat as opposed to a would-be Bonapartist dictator-in-waiting).

In the subsequent Russian Civil War, when a range of foreign powers and domestic opponents sought to overthrow the Soviet government, Trotsky was instrumental in creating the Red Army and as Commissar for War directing much of its ultimately successful strategy, fighting a four-front struggle. Traversing Russia in an armed train numerous times, unlike most other leaders on all sides he frequently risked his personal safety to direct and encourage the frontline troops.

|

| Trotsky speaks on top of his armed train |

Once it was over, he initially sought to return to his first love - writing on political theory and practice and history, including producing a four volume history of the revolution - but was persuaded to stay on in government by Lenin. With the country in ruins, Trotsky maintained a militarised approach to reconstruction and while the new socialist regime struggled for some time, his hard tactics began to work and industrial production began to rise again. He worked with Lenin to both nationalise and revitalise the economy, including backing the controversial New Economic Policy which briefly reintroduced small scale market economics while not veering from the aims of a socialised society.

Perhaps though one of the biggest tragedies of both the Revolution and in some ways the whole 20th century was that, following an attempted assassination attempt in 1919, Lenin became chronically and progressively ill, dying in 1924 - possibly hurried along during a visit from Stalin, his ultimate successor and an avowed opponent of Trotsky.

Stalin had started out as a sort of Bolshevik enforcer - he organised gangs of agitators and fundraised for the Party by carrying out bank robberies (NB - this was one of the few criminal activities Lenin sanctioned). He had always been in the background, almost invisibly so during the revolutions of 1917 but by 1923 had risen to be General Secretary of the Communist Party, a key role overseeing how it ran.

In the ensuing struggle for power within the party, Trotsky was repeatedly outmanoevred by the rising Georgian sociopath, first being expelled from the Communist Party along with several prominent supporters, then sent on internal exile to Central Asia and finally deported with his wife Natalia Sedova to Turkey in 1929.

In his final, prolonged exile, Trotsky first set up in Prinkipio, an island in the Sea of Marmora just off Istanbul, before subsequently having to move on to France, Norway and then to Mexico as government after government either objected to or feared his activities in the ferment that was 1930s Europe. He worked with relatively small groups of international revolutionaries to develop a counterforce within communism to the increasingly totalitarian Stalinist regime in the Soviet Union.

This he devastatingly critiqued in his work Revolution Betrayed, a searing indictment of the bureaucratization of the country, which he had repeatedly warned about in the earliest days of the revolution. A new class had arisen - one of administrators and managers, serving themselves rather than the People, and accountable only to itself. The democratic promise of the early Soviet days had all but evaporated and while he conceded that there were material gains for many ordinary people, these were both impeded and stolen by the new Masters.

Trotsky initially sought to avoid any split in the Communist movement. His stated aim was to restore workers' democracy rather than divide the party, but after Stalin ordered the German Communists to decline any Popular Front with the Social Democrats against the rise of the Nazis, in 1933 he agreed to create a new socialist movement, the Fourth International. This sought to promote a different path to a genuinely communist state, one where power was more firmly in the hands of the masses - though Trotsky's approach remained decidedly centralised, a conundrum in his thinking he never resolved. In any case, the Soviet system as it had evolved to be was to be dismantled and forged again.

In addition, while Stalin had reconciled with capitalist states, Trotsky argued that Communists should forever press for global revolution - given the state of the world, full revolution in one country was not possible; however challenging, permanent revolution had to be the objective of all communists until world revolution was achieved.

Brooking no opposition, Stalin consolidated his position as supreme authority within the Party and state in the early to mid-thirties before unleashing his Great Terror against his remaining opponents, real and imagined, in the purges of 1937. By the end of the year, virtually all the original revolutionary leaders had been eliminated within the USSR and, condemned in absentia, Trotsky was to be no exception. Spending his final days in a well-fortified house, Avenida Viena on the outskirts of the Mexican capital, he seems to have sensed his coming end, either from high blood pressure or at the hands of an assassin and while he resisted Mercader, in his reported final words, he seems to have been unsurprised by his pending demise at the behest of his one-time rival.

Volumes have been filled about Trotsky, a good number of them eloquently and passionately by the man himself - Trotsky's writings are rarely not an enthusiastically good read. Yet in spite of this, in many ways he remains one of the most enigmatic characters in revolutionay history. Loved and loathed by socialists of different hues, a genius to some while demonised, literally, by others, his stamp on one of the seminal events of modern history is unquestionable. While communists will argue that historical forces brought about the 1917 revolutions, as Trotsky himself wrote, while such forces are supra-personal, they nevertheless operate through people.

|

| Trotsky, Lenin and Kamenev in 1918 |

Here of course is where everything else moves to the what ifs of alternate history. What if Lenin had lived? What if Trotsky's struggle against Stalin had had a different outcome? What if the Soviet Union had developed along the more proletarian, democratic path he advocated? After the years of War Communism and central direction, how different from the totalitarian Stalinist state or the later Brezhnevite bureaucracy might the Soviet Union have ended up being, or not?

Trotsky, like any human, was of course full of contradictions. He fulminated against Stalin's banning of his Left Opposition faction within the party, but had previously supported Lenin in banning the Workers' Opposition and other factions opposing their strand of thinking. He denounced Stalinist totalitarianism, but had successfully opposed Lenin, a relatively unusual stance, in banning independent trade unions, arguing that such things were no longer necessary in a workers' state.

His own opponents often claim he butchered thousands of people in the civil war, in putting down the Kronstadt rebellion and in suppressing opposition parties in the early 1920s. Yet all this needs some context.

The civil war was a bloody affair. That is the nature of civil wars. All norms of behaviour are destroyed. Distrust rules and outcomes are rarely gentle. The Russian civil war began when Social Revolutionaries, Kadets and other so-called liberal parties decamped from Moscow and Petrograd to Samara in central Russia and set up the Komuch, a rival government, in June 1918. Co-operating with hardline White Russian Czarist generals and soldiers, as well as the Czech Legion, they launched a violent attack on the Soviets, with the avowed aim of liquidating the Bolsheviks who were then ruling in coalition with a faction of Left Social Revolutionaries.

Over the following three years, the Komuch largely ate itself - the rival liberal and socialist parties turned violently on each other and then, sponsored by the British Empire, the White "People's Army" turned on them and installed Admiral Kolchak as effective dictator. To portray their bloodthirsty campaigns and pogroms, armed and aided by a range of foreign states including the UK, France, the USA and Japan, as some sort of crusade for democracy and freedom is at best misplaced.

It is true that in reaction to the Komuch, the Bolsheviks suppressed, though did not initially ban, the remnants of these parties in their areas and after the Left SRs attempted to assassinate Lenin and carry out a coup d'etat in late 1918, the Soviet Government ruthlessly carried out a wave of often extra-judicial arrests, torture and executions. Even so, this should still be viewed as a response to the nature of the threat they faced, as was the continuation of oppression in the immediate period after the civil war ended.

Russia was grossly under-developed compared to most of the rest of Europe - it was the last place that Marxists had anticipated a socialist revolution. Initially favourable developments elsewhere in Europe, with Germany in revolution in late 1918 and early 1919, Hungary briefly declared a Soviet Republic, Italy going through a range of Red Uprisings and Leftist movements growing in France and Britain, gave hope for international revolution to follow the Soviet example. However, one by one these were suppressed and snuffed out, often with great violence, but the ruling class's hostility towards the New Union of Soviet Socialist Republics was undiminished.

With virtually the entire world ranged against the nascent workers' state and more than willing to use everything from economic embargoes to military intervention to overthrow it, the conditions sadly did not lend themselves to generosity towards rivals with murderous intent.

And yet, in the USSR, women gained marital equality and the right to divorce; it became the first country in the world to legalise homosexuality; the land was collectivised and the economy was taken into state hands. Ultimately, albeit not entirely by the means Trotsky himself advocated, in less than a generation and in spite of the worst war in history and the appalling carnage of the Stalin regime, the Soviets achieved free education for all, built houses for tens of millions, provided free healthcare and were the first country into outer space. Under communism, a peasant state had become a superpower in barely three decades.

Trotsky devoted his life to change: that he miscalculated on occasions, sometimes on a grand scale, does not diminish either his effort or achivements. He was flawed - even allies like Max Eastman, an American supporter, reported that while he observed every protocol of politeness and seemed to have little vanity, his global view of everything made him a detached, in some ways cold character often quite incapable of the diplomacy and sociability required of a successful politician. Typical of his bearing is the story that when Stalin attempted to make a joke to him about a relationship Alexandra Kollontai, a prominent female Bolshevik, was rumoured to be having, Trotsky angrily rebuked him and never spoke to him again in any personal way.

|

| Lenin with Stalin |

Yet with his sociopathic charm and crude bonhomie, Stalin was able to build coalitions that literally overwhelmed Trotsky and his earnest comrades in the Left Opposition.

And while his earlier exiles in Czarist Russia had been times of rising intrigue, his final exile in the 1930s was marked by years of impotent frustration, ranting to his small coterie of followers and staff. While damning Stalin for the rise of Hitler and his unwillingness to compromise with the German SPD, Trotsky was equally to be found blocking and condemning any co-operation between his own Fourth Internationalists and groups like the Spanish POUM, a temporarily highly successful anarcho-syndicalist force in the Spanish civil war. A reading of his deteriorating and increasingly irate correspondance with his fellow exile, the writer Victor Serge, is a striking example of how banishment did nothing to soften Trotsky and how his intransigence frequently isolated those who, somehow, continued to respect him from afar.

Trostky's son, Lev Sedov, commented that "I think that all Dad's deficiencies have not diminished as he has grown older, but under the influence of his isolation, very difficult, unprecedentedly difficult, got worse. His lack of tolerance, hot temper, inconsistency, even rudeness, his desire to humiliate, offend and even destroy have increased. It is not personal, it is a method and hardly good in organisation of work."

It is something much ruminated on - the revolutionary who loves The People, but not people. To Eastman, Trotsky saw the masses but not the personal; all was great forces in action with little regard for individuals who were the parts that made up the sum. And so he was allegedly capable of summarily ordering a roomful of revolutionary officers to be taken outside and shot in the belief that they had failed to carry out their tasks well enough, while at the same time issuing proclamations urging revolutionary soldiers to show mercy to any White combatants who surrendered so that they could be won over to the cause.

Yet while some revolutionaries like Gramsci wondered if having never experienced personal love diminished their capacity as a revolutionary, Trotsky was certainly capable of personal love. Contrary to appalling biographies that try to portray him as an unfeeling psychopath, he cared deeply for his children and risked his life to protect his grandson during one attempted assassination. His brief but passionate love affair with Frieda Kahlo aside, he was devoted to his wife Natalia (whom he also referred to as Natasha) for decades and one of his last pieces of writing offer up a moving tribute to her and what she meant to him, as well as his hopes for a future he by then knew he would not see. It is as beautiful a paean to a revolutionary life as could be penned and in itself is perhaps the best testament to the contradiction of love and zeal, of pragmatism and ideology that was Leon Trotsky:

I thank warmly the friends who remained loyal to me through the most difficult hours of my life. I do not name anyone in particular because I cannot name them all. However, I consider myself justified in making an exception in the case of my companion, Natalia Ivanovna Sedova.

In addition to the happiness of being a fighter for the cause of socialism, fate gave me the happiness of being her husband. During the almost forty years of our life together she remained an inexhaustible source of love, magnanimity, and tenderness. She underwent great sufferings, especially in the last period of our lives. But I find some comfort in the fact that she also knew days of happiness.

For forty-three years of my conscious life I have remained a

revolutionist; for forty-two of them I have fought under the banner of

Marxism. If I had to begin all over again I would of course try to avoid

this or that mistake, but the main course of my life would remain

unchanged. I shall die a proletarian revolutionist, a Marxist, a dialectical materialist, and, consequently, an irreconcilable atheist.

My faith in the communist future of mankind is not less ardent, indeed

it is firmer today, than it was in the days of my youth.

Natasha has just come up to the window from the courtyard and opened it wider so that the air may enter more freely into my room. I can see the bright green strip of grass beneath the wall, and the clear blue sky above the wall, and sunlight everywhere.

Life is beautiful. Let the future generations cleanse it of all evil, oppression and violence, and enjoy it to the full.

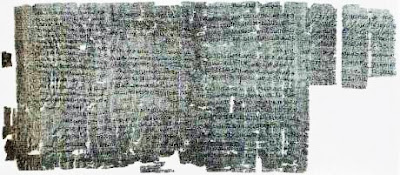

|

| Mexican exile: Natalia Sedova and Lev Davidovitch |